Stilts. What you think of when you hear that word depends on your experiences. Maybe clowns at the circus with extraordinarily long legs, maybe Carnival performers. I think of Liberia. I’ve never been to Liberia, mind, but when I was young, my parents acceded to my birthday wishes and took me to see an African dance troupe performing in Philadelphia. There were dancers aplenty, but the stiltwalkers were taller than anything I’d ever seen on the Ed Sullivan Show (yes, dating myself), and moved with a majestically supernatural grace, their long, mantis-like legs covered with striped fabric.

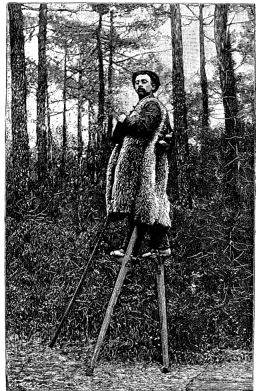

In many regions of the world, stilts developed for work purposes. French shepherds used them to navigate over marshy ground and have an elevated viewpoint for tracking flock members, while drywall installers and painters often employ them to avoid climbing up and down ladders. Even fruit pickers in California sometimes prune trees and collect their b ounty with ease of these elevators.

ounty with ease of these elevators.

Entertainment has also been a major stilting function. Millennia ago, the Chinese began to use them for imperial performances. European festivals that feature dancing or racing take place in Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands. The Marquesas Islands of the South Pacific used to have races, as well as a form of stilt fighting. The Japanese played with them, calling them takeuma (bamboo horse). Many American street fairs and parades use them as major attractions. Cleveland’s Parade the Circle annual event (second Saturday in June—a fabulous Cleveland Museum of Art festival that is certainly not just for children) trains stiltwalkers, and in the weeks before the main event, teachers and returnees awe those working on their costumes with acrobatics and even soccer games.

This Parade’s stiltwalkers have a geneology direct from Trinidad and Tobago, for its organizer, artist Robin van Lear, has for twenty years brought in international artists with long pedigrees in the island nations’ Carnival tradition. And this tradition is one that features moko jumbies, costumed stiltwalkers who have been a part of Carnival for two centuries or more. They were not restrained to Trinidad; in St. Vincent of the Virgin Islands, a “mocko jumbo” on stilts was recorded in 1791, an animal head covering the performer’s own.

Trinidadian (and Tobago!) users are not precise about which part of Africa

Nigeria’s Urhobo, Gabon’s Punu, the Ivory Coast/Liberia’s Dan, Mali's Dogon, groups in the Senegambia, Mali, Guinea, Ghana and elsewhere.

The African stilts are often 12 feet high, and always worn by men. They are frequently masqueraders, faces covered. In some areas they are considered messengers to the ancestors or spiritual guardians. In others, they are dancers only, albeit mysterious ones whose abilities, by consensus, are attributed to powerful supernatural medicines. When performances take place at night, their looming presence can be positively frightening—they lope along, casting odd moonshadows, as drummers beat for them.

For Saminaka’s upcoming African Festival, Oct . 1-4, 2009, stiltwalkers from several traditions will stride across the landscape, reminding observers of a powerful tradition that crossed the Atlantic, and continues to spread. Would you like to join us as a participant, rather than just an observer? Contact Tamsin Barzane inworld, or here on the blog!

. 1-4, 2009, stiltwalkers from several traditions will stride across the landscape, reminding observers of a powerful tradition that crossed the Atlantic, and continues to spread. Would you like to join us as a participant, rather than just an observer? Contact Tamsin Barzane inworld, or here on the blog!

To see a West African stiltdancer from the Dan people, see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7H9f0paCCo

To see “Mokolution”, a multi-part documentary from the American Virgin Islands about the tradition in both Africa and the Americas, see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nOU1TyYd_3U&feature=PlayList&p=516556F1AAEB4CE8&playnext=1&playnext_from=PL&index=1

No comments:

Post a Comment